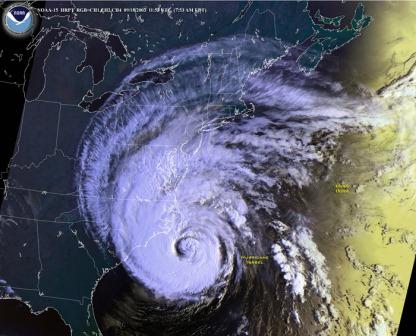

Ten years have passed since Hurricane Isabel tracked through the Chesapeake region with high winds and high water levels. Isabel made landfall near Drum Inlet, North Carolina, around 1 p.m. Thursday, September 18, as a category 2 hurricane with 100 mph winds. While crossing the Atlantic Ocean, Isabel had attained category 5 status; fortunately, it encountered vertical wind shear and lost much of its intensity before landfall.

Isabel was directly responsible for 17 deaths and indirectly for 34 deaths, and an estimated $3.37 billion in property damage. The storm affected portions of northeastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia with hurricane-force winds and a large area from northeastern North Carolina through the eastern Great Lakes and western New England experienced tropical storm conditions.

Around the Chesapeake Bay, Isabel is most remembered for storm surges that created record high water levels, rivaling water levels from historic storms including the Chesapeake-Potomac Hurricane of 1933. Because few people today remember the 1933 storm, most anecdotal descriptions of “how high the water got in the big storm” today reference Isabel.

Storm tide measured from 6 to 9 feet in the Chesapeake Bay area and tidal Potomac River basin. Isabel’s path—west of the Bay, moving toward the north northwest, roughly paralleling the Bay—meant that the counterclockwise winds pushed lots of water from the Atlantic Ocean into the Bay.

At 9 p.m. Thursday, September 18, the National Hurricane Center dropped the intensity of Isabel to below hurricane strength, but the leading right front quadrant of the wind field with sustained winds of at least 58 mph covered most of the Chesapeake, including the mouth of the Bay. For eight hours, onshore gale force winds pushed water directly into the Bay and prevented its escape.

As a result, areas including the U.S. Naval Academy and downtown Annapolis; Fells Point and Inner Harbor, Baltimore; Belle View in Fairfax County, Virginia; and Washington, D.C. experienced severe storm surge flooding. Here are a few of the storm tide crest observations (using the NGVD 1929—a sea-level reference mark—as the yardstick):

- Chesapeake Bay Bridge/Tunnel, Virginia: 7.12 feet above NGVD at 1:18 p.m. September 18

- Sewell’s Point, Virginia: 7.53 feet, 4:00 p.m., September 18

- City Locks on the James River, Richmond, Virginia: approximately 9 feet in late evening, September 18; even higher water levels were seen later when freshwater flooding from rainwater progressed down the river

- Washington, D.C.: 7.5 feet, 3:42 a.m., September 19

- Annapolis, Maryland: 7.47 feet, 6:42 a.m., September 19

- Baltimore, Maryland: 8.34 feet, 7:06 a.m., September 19

- Tolchester Beach, Maryland: 8.07 feet, 7:42 a.m., September 19

The overnight onset of the storm surge made the situation dangerous in many areas, because residents—at least those who were not awoken by the howling winds—slept as the hazards increased. Locations in the Shenandoah River Valley also experienced dangerous flash flooding resulting from Isabel’s rainfall, including storm totals of 8 to 12 inches with locally higher amounts.

High winds also contributed to substantial damage during the storm. Gloucester Point, Virginia, reported 60 knot sustained wind with a gust to 79 knots, while further up the Bay, Thomas Point Lighthouse off Annapolis reported 42 knots sustained and a gust of 58 knots. Power outages were also a significant outcome of the storm, as high winds and wet ground conditions combined to bring down many trees. Overall, about 6 million customers lost power—some for lengthy periods.

After major storms like Isabel, NOAA produces a report to examine the agency’s warning and forecast services and identify ways to improve services.

NOAA’s Hurricane Isabel Service Assessment noted that Isabel’s storm tide, in general, was 1 to 3 feet higher than what was forecast, especially in the northern Chesapeake Bay and Potomac Basin, pointing to a need for more robust computer modeling capabilities and more data points to feed those models.

While additional data and more comprehensive computer models have enabled meteorologists to fine-tune forecasts, enabling increased accuracy in forecasting storm track and intensity, forecasting storm surge continues to be an area that needs improvement; this was underscored in the Hurricane Sandy Service Assessment. Other service assessments, including that for Hurricane Irene, highlight a need to improve warning times, such as those for flash flooding.

Adding more data points to computer models can improve their accuracy. Buoys in the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System, which were deployed starting in 2007, provide 10 additional data locations that are used by meteorologists in their computer models and to develop marine forecasts. The environmental and coastal intelligence CBIBS delivers, including having hourly data from CBIBS buoys on wave heights in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay helps forecasters validate past forecasts, leading to better future forecasts of wave heights. While previously forecasters relied on historical data to set anticipated wave heights, now meteorologists can incorporate CBIBS real-time wave height data into models to achieve increased accuracy.

The Hurricane Isabel Service Assessment identified additional ways NOAA can help serve the public, including highlighting the dangers of carbon monoxide poisoning—often from improperly used generators—and improving the capability of NOAA Weather Radio transmitters to ensure uninterrupted service during severe storms. The Hurricane Sandy assessment echoed the need to improve communications of forecasts—and what they mean for more specific locations—to emergency managers and the public.